A never satisfied monk

Ideas of a conscious universe

A feeling of unsettledness has always lived in me, often resolving in choices and actions like mold spores blooming to life when conditions are right. Someone recently put a new name to that feeling when, only a few moments into the first real conversation we’d ever had, she recognized it and proclaimed to me, “You’re never satisfied, are you?” She then suggested I read Thomas Merton’s journals as he was never satisfied, either.

I had to admit I have never been easily satisfied. I was never satisfied with pat answers to my young self: “Sons go to construction sites with dad; daughters stay home and do housework with mom.” Never satisfied with reading only one book, answering only one question, considering only one option. Never satisfied with, “because I said so,” or “because it’s in the textbook,” or to even greater guilt, “because that’s what the church says.”

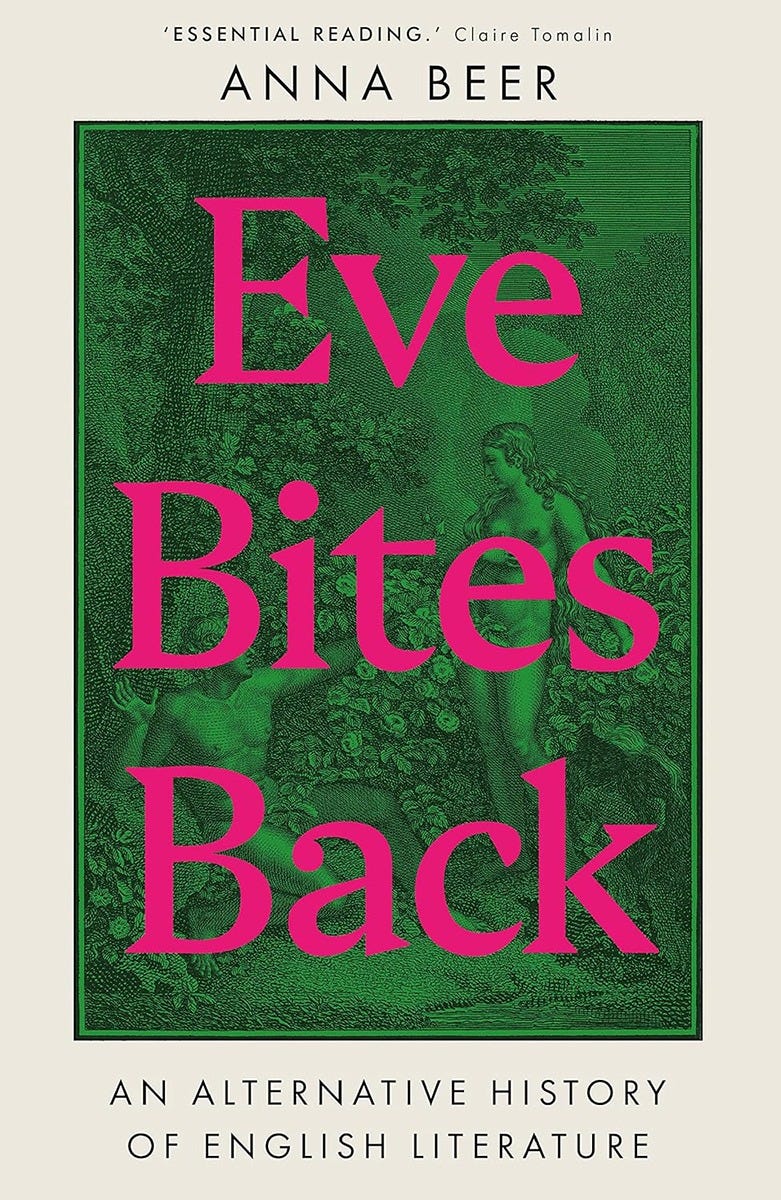

In the weeks since that somewhat disquieting conversation, I’ve read The Sign of Jonas, The Intimate Merton, and Eve Bites Back, An Alternative History of English Literature, (which called out to me from a display in an independent bookstore I visited on the drive back to Erie after the transforming conversations). I have realized that “never being satisfied” leads me to the same end as what Merton called “doing God’s will.” And it is how I am doing my part in human consciousness moving the Universe to become conscious of itself, as theologian and visionary thinker Ilia Delio writes.

Offering “God’s will” as an explanation for anything never satisfied me. Giving my heart to God, yes. But “doing God’s will” seemed hokey, like, who can ever know God’s will? Even as a young person I knew the power of my mind and how easy it is to convince myself that something is what it isn’t or isn’t what it is. And if I could do it, I had no problem imagining others could do it, too. What was self-deception, even if unintended, and what was truth? Maybe a moot question in an era of “true” fake news...

But I can see “never being satisfied” as how the God of the emerging Universe invites me to learn, to deepen, to abandon myself, to seek, to create, to connect, to become, to love. In the words of Merton’s older theology, that would be “doing God’s will.” And in Ilia Delio’s theology of a quantum and cosmological worldview, it is bringing to birth “the light-filled consciousness of God, the same light that coincides with the unfolding Universe.” (Read more at the Center for Christogenesis.)

I find deep meaning and hope in new theologies as opposed to the prescientific medieval theologies that still inform much of our thinking, societal as well as ecclesiastical, even though those ancient theologies are intellectually and spiritually inadequate for what we now know about the Universe. “Classical Christianity and its theologies first came to expression at a time when people took for granted that the universe is fundamentally fixed and unchanging. …theologians can no longer plausibly ignore the fact that the whole universe, not just life and human history, is still in the process of becoming.” —John Haught in The Cosmic Vision of Teilhard de Chardin.

For me, the pieces of past and present fit together and move toward the future in a surprisingly satisfying way when I open myself to a world bigger than the narrowly recorded past and welcome the possibilities of a future I can’t imagine. The becoming-conscious Universe has great ideas when we look and listen for them. For example, how can I doubt the unfolding Universe when I think about a girl-chasing, educated, world-wise young man abandoning everything to enter a cloistered monastery in the hills of Kentucky? (See the Seven Story Mountain, Thomas Merton’s autobiography.)

If the evolution of human consciousness is expanding to a Universe becoming conscious of itself, then the Universe, like any conscious being, becomes capable of having ideas. The life of Thomas Merton, then, was an idea of the Universe. Stop and think how the Universe shaped the trajectory of so many other lives through the idea that Merton was.

Was everything to which Merton said, “Yes,” necessary for him to become the idea of the Universe that gave so many such spiritual insight? Did the Abbey of Gethsemani need to be what it was, with its history, its forebears, the monks who shared life with Merton, for this particular idea of the Universe, this singular manifestation of God’s will, to emerge? Obviously so.

Likewise, the eight women authors Anna Beer reveals in Eve Bites Back were ideas of the universe that changed—albeit not yet enough—the world we now inhabit. These women who were not satisfied with the status quo lived and wrote between the 14th and 19th centuries and only through slim chance have their words come to us. Anna Beer herself, not satisfied with the erasure of women from history, is also an idea of the universe who carries evolution further by uncovering and calling out the misogyny, literary patriarchy, and cultural constructions of patriarchy that all but eliminated the insight and richness of these—and so many other—women throughout history. Why fear the future when the Universe has such great ideas and somehow manages for them to survive and seed new ideas?

Every thinker, inventor, visionary, leader is an idea of the Universe coming to consciousness. We are all to greater or lesser degree ideas of the evolving consciousness of the Universe. Are we unsatisfied enough to ask bigger questions, to seek challenging relationships, to dig deeper into what gives life meaning, to risk trusting the unknown? Are we able to recognize in our daily lives how the Universe is preparing and shaping us so that we, too, become ideas that shape the unfolding, not-yet Universe in significant and hopeful ways?

The Fifth Kind of Monk is one of the infinite still-emerging ideas of the Universe. I can see that not being satisfied even after my thirty years in the monastery (Thomas Merton expressed similar sentiment after twenty-seven years at Gethsemani.) is not a reflection of lack of commitment or insincerity or even self-deception. But rather the lack of satisfaction tells me that making a commitment to give my heart to God is not fulfilled once and for all nor is it satisfied by geography or the following of certain rules, even religious rules. I must make a continual, conscious choice to become more fully human in relationship with others, our world, and God. To be the idea, the love, that will bring the Universe closer to its fulfillment. Living in a monastery can help, but it is no guarantee. We need the Fifth Kind of Monk outside the monastery, too, and the ideas the Universe will have through this kind of monk.

Note: Benedict wrote of only four kinds of monks 1,500 years ago, two of which he considered detestable. You can read about them in the first chapter of his Rule of Benedict. The Fifth Kind of Monk is a new kind of monk moving us toward the not-yet Universe.

I'm delighted to learn there IS someone I know and gets the not-yet concept - (I tend to reference as kairos) - Hurray - I'm not alone!

The paragraph on p. 205 in Delio's The Not-Yet God, is huge to my understanding more accurately of the experiences so frequent in my life these days. As I near the end of this book I am quieted and more content in examining my life and determination to continuing to evolve even though the kind and intensities of pain persist particularly in looking around me. Being only one is enough - it is everything I am and will become.