While all of life is a massive learning experience, there are a few moments in most lives that stand out as learnings par excellence.

One such moment for me happened circa 1986. I was not quite thirty and in my first year of working in Montería, Colombia, with the Archdiocese of Denver mission team. The local bishop, Monseñor Darío Molina, a European-educated Colombian, had asked me to join the Oficina de Pastoral Social staff, akin to working with Catholic Charities in a U.S diocese.

Monseñor Molina summoned me to his office where I sat in front of the large, meticulously polished and clutter-free desk behind which he sat in his equally meticulously pressed and buttoned white cassock. My guess is he saw me as a naïve but sincere North American Catholic girl who, following the call of Jesus to serve the poor, had landed in the barrios of his diocese. He wasn’t wrong.

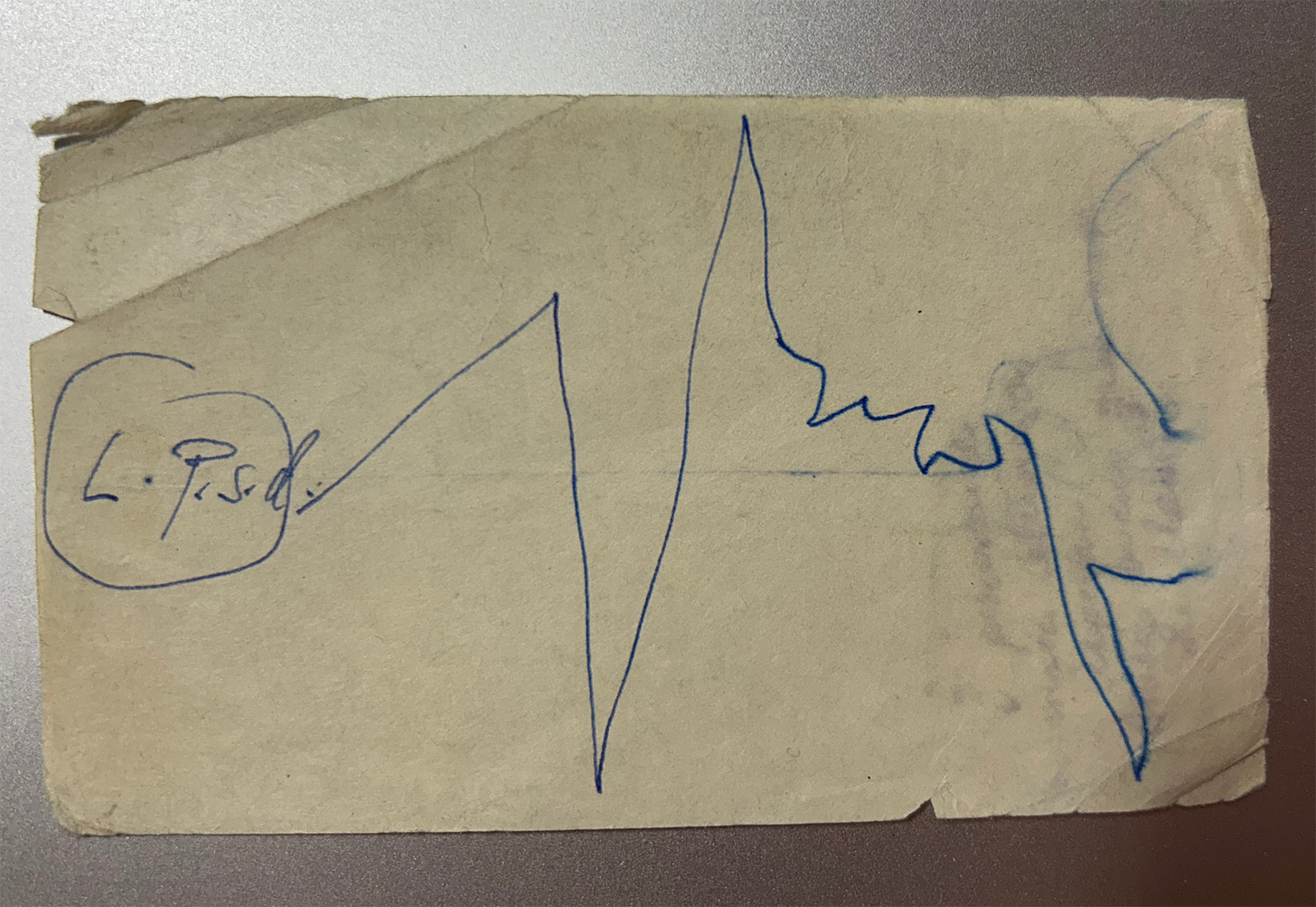

He put a small square of paper on his desk and proceeded to tell me that the Latin understanding of “rules” was like the jagged and irregular line he then drew on it. Getting from a start point to an end point in his culture was like that line, he explained. They eventually got there, but the route could be circuitous. Rules were guidelines to help them arrive. He then turned the paper over and put a dot at each end and drew a straight line between them as he continued, “and this is how North Americans and western Europeans get from one point to the other.” In our culture rules are often seen as absolutes, not mere guidelines. We focus straight-on at the goal and go for it no matter who or what gets in the way. We say what we mean, and we mean what we say.

I kept that paper, you can see one side of it here. With no desire to stereotype, I can say the insight he gave me into recognizing that culture affects thinking which affects behavior allowed me to connect at a deeper level with the Colombian people with whom I lived and worked. The greater impact for me, though, rested in grasping the concept that our words and actions become distorted when our thinking is either too rigid or too unrestrained. I gradually learned to examine and broaden my thinking as a regular practice. We are not the products of straight lines even though sometimes we act like that is so.

But we do need guidelines, life is not a free-for-all. The question is, on what are the guidelines based? On the ideologies and isms that shape our thinking today or the universal truths that spiritual visionaries have articulated and developed over millennia? I choose the spiritual visionaries whose wisdom has and continues to reveal itself in exploring spiritual experience, thinking about God (or however one names the Divine Presence), the miracles of the natural world, ongoing scientific discovery, and evolving human consciousness.

I live that choice by following the 1,500-year-old Rule that Benedict wrote as a guideline for those of his era who made the same choice I did. He filled it with exceptions, flexibility, and cautions knowing that life is not a straight line. However, sometimes it feels like we want to make it an absolute as if there is only one way to be Benedictine.

The balance and flexibility Benedict built into the rule makes the Fifth Kind of Monk possible. Benedict invites us to mine his spiritual vision for universal truths and then put practices into place that can serve as guidelines for us today. There is no straight-line way to live Benedictine life and living as if there is can suffocate a monastery. We must take the initiative to find and build on the zigs and zags so that we can offer this guideline to others who have nowhere else to go.

In a section on Teilhard de Chardin in his book Christ of the 21st Century, Ewert Cousins writes, “When human persons transcend themselves in love for others and at the same time affirm their own uniqueness, they are sharing—within the limits of their finitude—in the ineffable Trinitarian mystery in which distinction and union are had in absolute fullness.” He quotes Chardin directly from The Human Phenomenon, “Love alone is capable of uniting living beings in such a way as to complete and fulfill them, for it alone takes them and joins them by what is deepest in themselves.”

And that, dear monks, in my opinion is the purpose of a monastery: to support each other in our effort to be love for the world. Benedict told us our way must be different than the world’s ways. This is how we are different. It’s much bigger than following rigid rules.

Before I close, I want to ground our love in reality because the love that unites is hard work and doesn’t guarantee warm fuzzies. So, here’s some reality from my friend Tom Roberts, former executive editor of the National Catholic Reporter. He uncovers much frightening straight-line thinking in his piece, “Is Trump administration 'the most Christian' ever? No, it's not. Here's why.” Tom’s words are a clarion call for anyone who looks to Jesus as teacher and guide rather than those who want “to make unrestricted capitalism compatible with Catholic teaching.”

May all of us reflect on our life-shaping moments and recognize guidelines to love in them as we continue to seek monks and others to walk with us through the circuitous ways of God. And let us remember that it is Love alone that we monks seek.

Circuitous route indeed in “real time”, but the map of love is fixed…we stray, veer off course, then pull out the map once again to find our way.